If you are reading this I imagine it’s because you are suffering yourself from a herniated disc. I was there too, and still am 2 years later. While I’m not a doctor, and ask you not to take this as medical advice, I hope you might gain something from my experience. My first five lessons that I wrote when I was just 3 months in remain cogent and apt, are a story without an ending. As the injury transitions into a memory rather than an urgent priority, I should leave this map for who ever finds it useful.

Herniated Disc Recovery: Pain Ranges over Time.

Herniated Disc Recovery: Pain Ranges over Time.

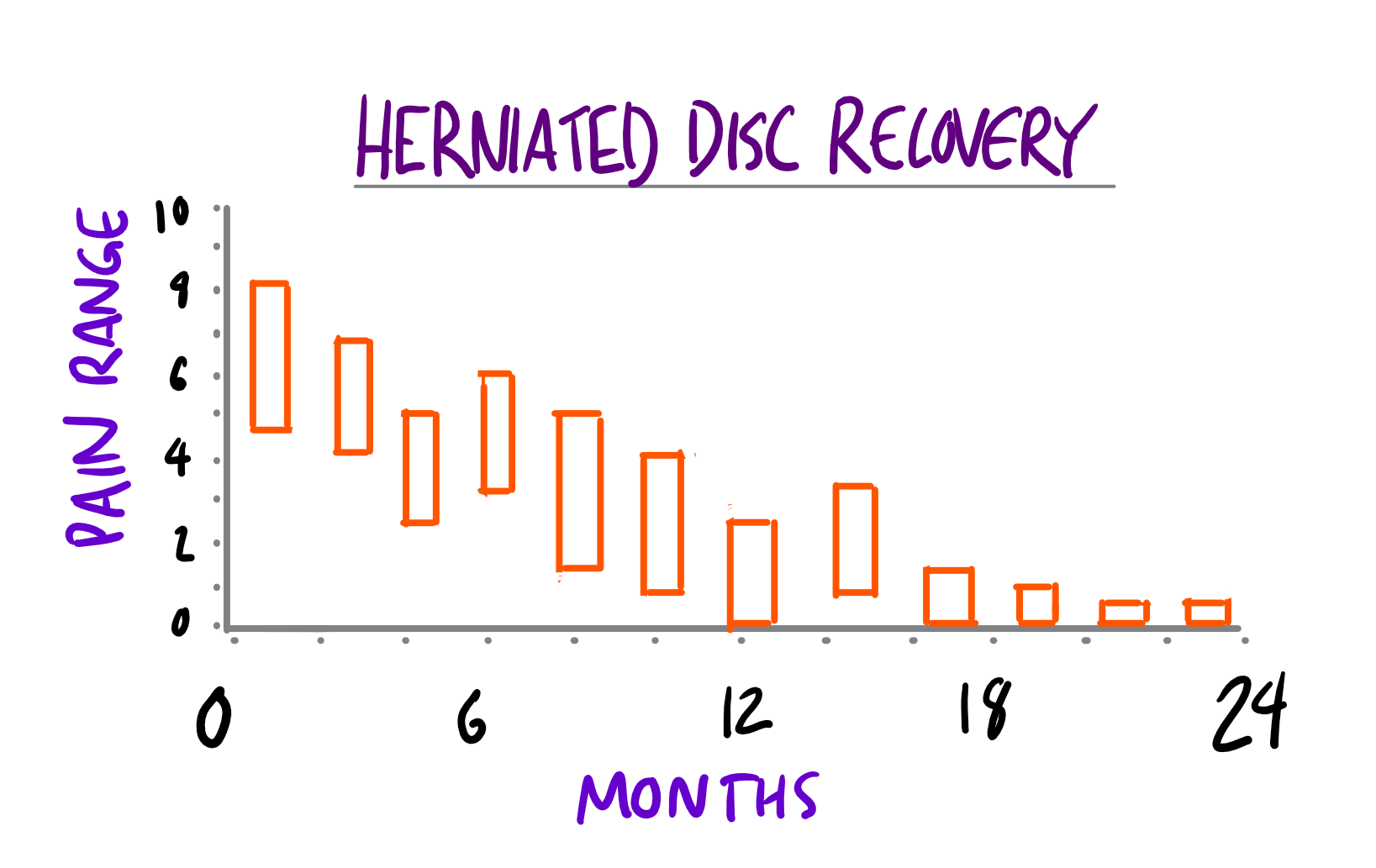

Above is a graph of the changes in pain over time I’ve felt after nearly 2 years of healing my herniated disc. On the x-axis are the months since I carelessly jumped off a tall platform, and on the y-axis is a standard 1-10 subjective pain measurement. The surprising facts about this graph that I couldn't have guessed before hand are that it 1) is a series of ranges of over time, 2) does not include 0-pain during the first year, 3) is non-linear and non-monotonic, 4) constitutes 2 full years.

The first aspect I’d bring attention to is that isn’t not a line, it’s a sequence of ranges. While it’s true that at any single point in time there’s a single pain level, the pain varied hour-to-hour, day-by-day, so for any week the “average” pain I felt was less important the extreme values. During the first 6 months I was constantly feeling a lot of pain, I wondered if I was ever going to get better? Adding to this doubt was the fact that sometimes my maximum pain was more than my previous weeks, having slipped putting on underwear or another mundane act gone wrong.

However, after a while I did notice I would have moments of low pain, maybe a 4 or 3 on the scale. This insight was the key to finally understanding that I would eventually start not-feeling pain again. As I saw that those moments were increasing, then I could see that I was improving, albeit it at a glacial pace, and even if I had days of relapse.

Only now can I sketch in the final details of the limits on the time-axis. I both scoffed at and denied in my first months that this injury could take 2 years to heal, as my Physician-father-in-law kindly advised me. That’s at least 4 times as long as any other injury I’ve had in my life. I don’t scoff at the duration today like I did before, rather I’m glad that it’s a finite duration at all. I'm sure that's little consolation to anyone with a recent herniation, owing to what I call the "pain trap".

Simply put, this a long and painful injury. I was in nearly constant pain for at least 6 months, a scenario that satisfies many definitions I can see online for “chronic pain.” Today, even though to a much lesser degree, I still experience flare-ups. It took me a lot of time though to understand nature of pain, and how it constitutes a mental trap.

I best understood what pain was doing to my psyche when I heard pain described as an “interrupter.” That is, it’s a biological process trying to get your attention. And in this case it was trying to get my attention all the time. That made it difficult to focus on anything else. This is where the trap is sprung because healing takes planning and a scientific mindset that requires exactly the kind of rational attention that pain interrupts.

For instance after 6 months I began to notice that I hadn’t even really researched how to best heal my condition beyond a single visit to the doctor—and I am a professional researcher. I realized I hadn’t conducted real experiments with equipment, exercise or diet. Being in pain, I would simply lay on the floor and try to distract myself TV. While it was immediately relieving, I don’t think it was the maximum “healing” it could have been if I approached it with a clear mind. Once my focus returned in drips and drabs I was able to really try to troubleshoot the herniation. In parts 3 and 4 I share every technique tip and hack that I attempted, but there is one more than others that deserves special attention—laying down.

Research shows that laying down is the position that puts the least pressure on the inter-spinal discs [1]. So I did that as much as possible—and more than what is perhaps "normal" in polite society. In general the question of my life became, "can I do it laying down?"

Working laying down, on the cheap with a folding laptop stand.

Working laying down, on the cheap with a folding laptop stand.

The biggest gain in laying-down time was in work. Luckily I have a job that involves using a computer most of the time, and $20 laptop stand made the switch possible. The harder part of working laying down was explaining to colleagues why I was doing it for the hundredth time.

It didn't stop there, what about eating? At home I ate on my laying on my stomache, with a yoga bolster under my chest to gain some elevation. At restaurants, if booths were available that was a good opportunity to channel an idealized version of an Egyptian Pharaoh and dine at a half-elbow-prop . In cars and Lyfts, if possible I would ask for the front passenger seat and recline, all the way if possible.

After being horizontal, the next best is completely vertical, and I would stand on my morning tram commute even if seats were open. Once I spent all 4 non-take-off hours of a flight standing in the aisle.

I would be remiss, if I didn't credit Raquel Meseguer and her opinions on vertical culture for emboldening me. Further, excellent listening on the hegemony of sitting in this Modern Mann podcast episode. I'm lucky to have just been a tourist in radical laying down, Raquel who is there more permanently is a strong and inspiring layer. For me laying down a lot was half the battle, and experimenting with all the other tips was the other.

It can't hurt to try everything. It hurts more not too! It served me to be creative and holistic in my thinking. In order to illustrate that point best, let's inspect a list of everything I tried.

Sleep, how on earth could you get a good nights sleep when you can't turn the pain off? The answer is might be "in a way you are totally unaccustomed to." My habitual side sleep was not the least painful, it turned out. A few youtube physiotherapists recommended sleeping on the back with a lumbar support, a.k.a a towel rolled up. It took me several difficult nights to train myself to fall asleep on my back, and more again to find the right lumbar support height, but it did pay off.

Exercise was a difficult healing technique to get right. On the one hand I found it to be useful because it regulated my mood and kept me positive. On the other hand it sometimes didn't appear to aid healing or would regress my condition.

If I felt up to it, the gentle exercises that I found I was able to do were:

Sadly, most things more demanding than gentle stretching hurt early on. Everyone of the following activities made me feel worse and I believe I exacerbated the pain typically for approximately the first 9 months to a year:

What about the promise of better living through chemistry? I was prescribed 2 pharmaceuticals during my only doctor's visit. They were:

In addition to Naproxen, here are the other over-the-counter and holistic remedies I tried.

I remember a week into the injury staring in disbelief at a 2 year recovery period. Today I'm grateful that I didn't elect for a surgery, walked (layed) the long road and learned these humbling 10 lessons along the way. In this article I've tried to avoid giving advice and kept the focus on my own story. If you're still reading, it's because I imagine you are on the floor despairing as I once was. So I'd like to offer my story as a data point, and as a point of optimism. My injury was an arduous journey, but it had meaning, and a was a platform for self-discovery toward the end. I'd be glad to lend you a sympathetic ear on IG @spinal.chat if you can't yet see that end in sight.

Herniated discs are not confusing,

Max