Hostbot-AI: Finding Promising New Users in Wikipedia with Machine Learning

By max, Wed 20 November 2019, in category Research-notes

By max, Wed 20 November 2019, in category Research-notes

Many thanks to my collaborators Jonathan Morgan, Aaron Halfaker, and colleagues at CATLab for their support on this project.

Can machine learning identify and connect the best newcomers to Wikipedia with mentors and keep them editing for longer? That's what I aimed to find out during my stint with the Wikimedia Foundation Scoring Platform Team.

Matching newcomers with mentors is seen as a promising way to help reverse Wikipedia's trend in declining active editors. But because they are a volunteer human resource we ought to wisely use their time. A heuristic model has been the way that newcomers are invited to the English Wikipedia TeaHouse for 4 years, but ideas to improve upon it with AI have floated around. Based on the ORES platform, I labelled the data for, and trained a new model to predict the potential of a new user after their third edit. Then in a 6-month long A/B test we saw if it could increase retention of newcomers against the heursitic model as a baseline. The results which came from inviting over 10,000 real-world users were unfortunately mixed. In the short and medium-term users identified by AI came back more often, but perplexingly the reverse was true in long-term analysis. The results demand further investigation, but still a lot of machine learning models and key technology was built along the way.

Wikipedia is facing a decline in active editors, which is why addressing the problem of retaining new editors has received so much attention over the past decade. One popular solution has been the Tea House where users can get help from a real human. But owing to the fact that the teahouse is run by volunteer editors, inviting the users that will make the best use of it is a key challenge. Right now invitations have happened via HostBot, which invites newly-registered that have made at least 5 edits in their first day, and randomly subsets those users to a maximum of 300 invitees. Is the heuristic of 5 edits arbitrarily filtering out some good users, and is the random-subsetting leaving opporunity on the table to take the best users? Machine learning has the potential to address both of those issues.

Wikimedia's Objective Revision Evaluation Service (ORES) is a predictive algorithm that can already predict the quality of single edits and articles, this project extended that capability to sessions of multiple related edits. As this was a supervised machine learning problem, I created and labelled a dataset 1,000 sessions, using the Wikilabels system, committing a new labelling class back to the project as detailed on-wiki here..

The features that I engineered to predict a session were:

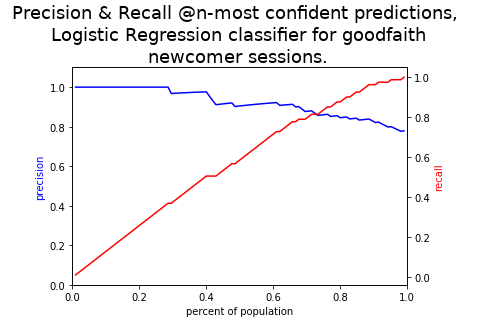

Finding an appropriate model of course first started with our metric selection. The metric used for scoring was precision at k=300, which mirrors the domains problem of choosing the best 300 editors to invite each day. I then ran Rayid Ghani's classic magicloops method of finding hyperparamaters and models that maximized the metric under cross validation.

Both gradient boosting and logistic regression appear to achieve approximately 95% precision in the top 300 most confident predictions, and cross-validation appeared steady. The prior for the goodfaith class is approximately 74% (most newcomer sessions are goodfaith) so we are definietly learning something above baseline.

The model was now trained and ready to be integrated into our experiment in production.

Exact details on the training can be found in the open source library, P.S. the session-oriented scoring is coming soon back upstream into the official ORES service.

With the help of TeaHouse hosts we decided to conduct an A/B test live on Wikipedia between HostBot (which from here on I also refer to as HostBot-heuristic when ambiguous) and HostBot-AI. The randomization coordination happened such that both where operating at the same time, but HostBot confined itself only to intervene on users with odd-numbered user-id's and HostBot-AI for even-numbered user-ids. Furthermore both limited themselves to inviting 150 users per day each to avoid inviting more than 300 users total to the TeaHouse on a given day. We used two sets of retention measures, to determine if outcome of the experiment. The first came the 2015 HostBot introduction paper which proved that the heuristic algorithm increased retention above control. Notice that in this experiment there is no true control for both the intervention to save on statistical power and utilizes this previous fact. In this experiment we also added more standardized survival measures. Further key decisions we had to make were whether HostBot-AI should a) wait for users to make 5 edits before predicting them, and b) invite them on a 24 hour cycle like HostBot heursitic. We were excited to see how useful the speedier potential of AI was, so we in the end decided that HostBot-AI would predict users after their third edit, and run every hour. Even though these decisions made the invitee groups have different demographic characteristics, the question of 'which technique is better at selecting the top-300 daily new users?' could still be answered.

The number one concern that Wikipedians have for Wikipedia are to "retain" newcomers, that is to have them continue editing after their initial joining—this is also known as "survival". The official retention measures from the Wikimedia Foundation are defined by a "trial period" (the inital spurt) the "suvival period" (when they return) and how many edits in the survival period define a return (see a detailed explanation here). We also used some traditional survival measures to see how many days on average a user remained active after intervention.

Conducting power analysis we found that for an 80% chance of seeing retention increase from 3% to 4% we needed 11,000 users per group. At a rate of 150 users per group per day, that meant we needed 73 days. To round this number we asked the community for a 90 trial period to run the experiment, which was granted and started on Feb. 1 2019. More details on power analysis can be found on phabricator.

I wrote the HostBot-AI code borrowing inspiration from the CivilServant, which I contribute to for work. It is essentially a once-hourly cron-job, that gets the registered users of the last 24 hours and predicts their non-damaging-ness if they have 3 or more edits. Users who are not initially invited, are re-evaluated every time they make more edits, until they either qualify for invitation or phase out of being newcomer after 1 day. Users who qualify after our 150 user quota were not invited, but marked as "overflow", the idea of which was to create a control group specific to the AI-invite. However only 50 users were collected as overflow, and so unfortunately we couldn't get statistical power from it. It was deployed in the Wikimedia Labs infrastructure, with much thanks to Wikimedia Cloud team. The production run went smoothly and accurately. In sum, 8,141 users received messages from HostBot-AI (and 56,06 users received messages form HostBot-heuristic). I would hope to re-run the experiment or deploy HostBot-AI for longer again using the same infrastructure. The bot's code is seperate from the modelling code and is available at https://github.com/notconfusing/hostbot-ai.

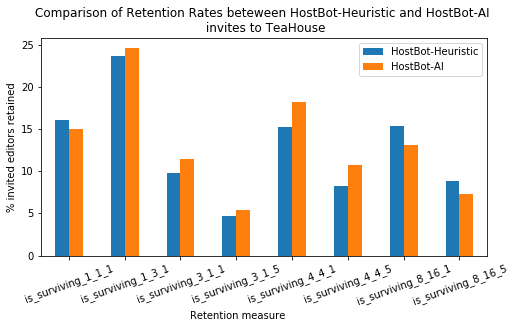

After our data matured. Our first stop was to re-run the measures that were used in the HostBot introduction paper that showed that the heuristic measure could beat a control group in retention. These measures come from the 2015, and have three components. The trial weeks are the number of weeks after registration, the survival weeks are the window after the trial, and the edits are the number of required edits to make to be considered survived.

| trial: survival:edits | ai_heur_per_diff | p_value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 : 1 : 1 | -1.076 | 0.467 |

| 1 : 3 : 1 | 0.912 | 0.026* |

| 3 : 1 : 1 | 1.750 | 0.000* |

| 3 : 1 : 5 | 0.620 | 0.053 |

| 4 : 4 : 1 | 2.935 | 0.000* |

| 4 : 4 : 5 | 2.425 | 0.000* |

| 8 : 16 : 1 | -2.261 | 0.010* |

| 8 : 16 : 5 | -1.459 | 0.026* |

What we see from these set of results are that AI-invited were retained more than heuristic-invited users by about 1-2 percentage points in the short (4 week) and medium (8 week) term. Meaning, for example that 16% were retained rather than 14% in the 4-week trial, 4-week survival, one-edit case. Perplexingly the trend reverses in the 24 week time-frame. Except for the extremely short term measure all theses differences are statistically significant under a t-test.

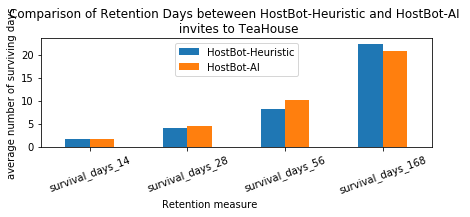

As well as the Wikipedia survival measures we ran more standard survival measures, that ask, in a given time window. What are average number of surviving days in each group? The number of surviving days are how many days after starting the user made their last edit within the window.

| heur_measure | ai_measure | ai_heur_improvement | tstat | pval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| survival_days_14 | 1.776 | 1.712 | -0.064 | 0.976 | 0.329 |

| survival_days_28 | 4.070 | 4.527 | 0.457 | -3.014 | 0.003 |

| survival_days_56 | 8.363 | 10.107 | 1.744 | -5.595 | 0.000 |

| survival_days_168 | 22.456 | 20.780 | -1.676 | 2.121 | 0.034 |

Here we can see that with a 14 day view, we don't have statically significant differences. Under 28 and 56 day windows, the AI-invited users stayed for half-a-day and almost 2 days longer, respectively. Yet, again in the long-term, with a 168 day view the trend reverses and the heuristically-invited users tend to stick around more.

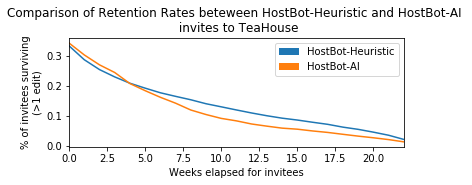

Another good view of these dynamics can be seen comparing the survival cures of the techniques.

For completeness, to test the significance of the difference between these two curves a negative binomial regression I believe should be run, which is future work for now. Still, visually you can see the short/long-term differences play out here again.

For full analysis of results, please see the full analysis on the Wikimedia PAWS public server.

In general, the results tell opposite stories depending on how we look at them. If we had only worried about the measures up to 8 weeks after intervention the AI would have shown useful, but on the order of 3 months, it seems like it is not improving retention. This begs the question of why the long term/short term differences? In our eagerness to launch the experiment we introduced several confounds at play that now need to be teased out.

With the notion that Wikipedians are "born not made", one possible explanation that Jonathan Morgan offered is that "we know that some people are likely to become long-term Wikipedia editors whether or not they get sent a Teahouse invite. These people make more edits in the first day, and get blocked/warned at a lower rate than other newbies. The HostBot-heuristic invite sample likely contains a larger proportion of these people than the HostBot AI sample, because they have to make 2 more edits to qualify, so some additional winnowing has already occurred." Therefore in the long run, with the qualifying edit difference, more "born" Wikipedians survive, but the reason that we don't see this effect in the short term is that the AI and speed effects are dominating, working on prone-to-be-made Wikipedians.

We built a new machine learning model to identify promising new Wikipedians, and employed it in a live field experiment against the current techniques. Our results show promise in the short term, but left a mystery as to the long term effects. Our attempt to try test several mechanisms as once: the minimum number of edits for inclusion, and the timing of the message sending, confounded our core prioritization method in unexpected ways. If you would like to discuss future directions, let's collect ideas for the next experiment on-wiki at Meta, https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Research:ORES-powered_TeaHouse_Invites.